Kay Warren cofounded Saddleback Church with her husband Rick, and they served there until Rick’s retirement in September 2022. After the death of their son, Matthew, who lived with serious mental illness for most of his life, Kay founded Saddleback’s Hope for Mental Health Initiative. In 2019, Kay started BREATHE, a ministry to support parents of children with serious mental illness.

Glen Bloomstrom is director of Faith Community Engagement at LivingWorks Education where he partners with faith leaders, seminaries, denominations, and Department of Defense and veterans’ groups to prevent suicide through education and intervention training. He is also a member of the Faith Communities Task Force, which leads the Action Alliance in efforts to engage faith communities in suicide prevention.

“The Stetzer ChurchLeaders Podcast” is part of the ChurchLeaders Podcast Network.

Other Ways To Listen to This Podcast With Kay Warren and Glen Bloomstrom

► Listen on Amazon

► Listen on Apple

► Listen on Spotify

► Listen on YouTube

Transcript of Interview With Kay Warren and Glen Bloomstrom

Kay Warren and Glen Bloomstrom on The Stetzer ChurchLeaders Podcast.mp3: Audio automatically transcribed by Sonix

Kay Warren and Glen Bloomstrom on The Stetzer ChurchLeaders Podcast.mp3: this mp3 audio file was automatically transcribed by Sonix with the best speech-to-text algorithms. This transcript may contain errors.

Voice Over:

Welcome to the Stetzer Church Leaders Podcast, conversations with today’s top ministry leaders to help you lead better every day. And now, here are your hosts, Ed Stetzer and Daniel Yang.

Daniel Yang:

Welcome to the Stetzer Church Leaders Podcast, where we help Christian leaders navigate and lead through the cultural issues of our day. My name is Daniel Yang, national director of Churches of Welcome at World Relief. And today we’re talking with Kay Warren and Glenn Blomström. Kay co-founded Saddleback Church with her husband, Rick, and they served there until Rick’s retirement in September 2022. And after the death of their son Matthew, who lived with serious mental illness for most of his life, Kay founded Saddleback’s Hope for Mental Health initiative. In 2019, Kay started breathe, a ministry to support parents of children with serious mental illness. Glenn’s director of Faith, Community Engagement and Livingworks education, where he partners with faith leaders, seminaries, denominations and the Department of Defense and veterans groups to prevent suicide through education and intervention training. He’s also a member of the Faith Communities Task Force, which leads the Action Alliance and efforts to engage faith communities in suicide prevention. We want you to be advised that our conversation addresses mental illness and suicidal ideation. If you or a loved one is struggling with suicidal thoughts, call 988 for the National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. Now let’s go to Ed Stetzer, editor in chief of Outreach Magazine and the dean of the Talbot School of Theology. Well, of course.

Ed Stetzer:

This is a it’s a it’s a sobering but essential topic for us to, to, to talk about and for for pastors and church leaders, as you know, when it comes to mental health crises, you pastors, which are our audience pastors and church leaders or the police tend to be the first responders in so many mental health crises. And when we talk about suicide and people who’ve died by suicide, um, we of course, I mean, Rick Warren in some ways put this conversation in a place where we could talk through, think through, through their own pain, um, to talk through and think through how we might respond simultaneously. I think ultimately that conversation does ebb and flow, unfortunately, often around traumatic events or, you know, well-known or well publicized persons who have died by suicide. So but the reality is, if you’re a pastor or church leader, and that’s probably who you are, if you’re listening to our podcast, this is a very real, ongoing part of your ministry, and I want you to be we want you to be prepared. We want you to be aware. So we are really privileged to have two key thinkers and leaders in and around this space. You probably Kay’s name will probably be more familiar, but. But Glenn has been working in multiple places in and around these questions of of how to serve well in these times. So let’s, let’s, let’s start by talking first with each of you. Maybe we’ll go to K first and and maybe K maybe in some ways I’ve already introduced. But why are you still involved in this conversation? Because I mean, this could be the kind of conversation that someone had walked through. The pain you walk through would step back from.

Kay Warren:

It’s very personal. It’s just so personal. I can’t say it more clearly than that. Um, I have had three really close experiences, let alone all the pastoral care experiences. My next door neighbor left me her suicide notes note, and I stood by her bedside as she died. Um, my cousins, my dear cousin’s husband, a pastor, started drinking after he got into financial difficulty and found no safe haven in the church for his struggle, and he took his life. And then just two years later, after that, my son, as you mentioned, Matthew, after 20 years of struggle with mental illness, took his life on April 5th, 2013. And so it’s personal. These are people I love. These are people that meant something to me and that their lives became so painful and unmanageable, and they felt they could not go on. Um, they’re really just a microcosm of the millions of people, million people around the world, about 51,000 or so in the United States who take their lives every year. And it it’s a hard topic. You said it at the beginning. It’s a hard topic to talk about. But just because it’s hard doesn’t mean it’s not vitally important. So that’s why I’m still involved. That’s why I still care.

Ed Stetzer:

Well, I’m glad you do. And, you know, I mean, we had something over 50,000 people a year. Um, you know, this would be something that consistently impacts churches, communities and more. So, Glenn, your story may be less familiar to us. So tell us a little bit how you stepped into this space, why it matters to you.

Glen Bloomstrom:

Well, my, uh, my experience with, with this topic began as a as a young chaplain in the early 80s, encountering soldiers with a variety of issues. Post-vietnam. A lot of veterans at that time. So I, I encountered many things that we needed skills to do that really, I hadn’t learned in seminary. And so over time, uh, after a career, I was sent to a graduate program by the United States Army. And then I served at the Pentagon, where I was responsible for suicide intervention training for the Army chaplaincy. We encountered a program that was not just informational, it was skill based. And when we saw that, we knew that was the program we wanted to have. And really, since about 2002, we’ve been able to train almost 600,000 in DoD in various locations around the world, even in combat. And I retired in 2011, but prior to my retirement, my second to last assignment, I had a young chaplain that was very, very dear to me. He had worked with me in the Pentagon, and I knew his family history, his story, and we were assigned doing lessons learned in Iraq, going kind of back and forth. And and he died by suicide. And he knew all of this material. So, you know, it’s kind of a personal thing, like Kay said as well, to lose a dear friend who was also a pastor, a chaplain. And so since I retired, I’ve taught in seminaries and I work for a living, works now for about 12 years, uh, to, to bring these same programs more so into churches and seminaries and other kinds of ministries. Wow.

Daniel Yang:

You know, both of you have been involved in this work for some time. And I’m curious as to what you’ve seen in terms of changes in trends, in how Americans, but specifically church, how we think about mental health challenges generally, but in specifically around suicide and suicide prevention. Kate, let’s go to you first and then we’ll go to Glenn.

Kay Warren:

Well, I’m newer to this than Glenn, but in the 11 years that I’ve been an advocate for people living with suicidal thoughts or suicide prevention and mental health, I have seen some really amazing changes. I know Ed and I talked, you know, soon after Matthew died and, um, just the the attitude in most clergy was, we don’t talk about this, you know, we don’t talk about mental illness. It’s of the devil if you pray more, if you, you know, confess your sins, if you join another Bible study, if you just love Jesus more, your mental health problems will go away. In fact, there is no such thing as mental health problems. And suicide was such a taboo, you know, even 11 years ago. And to see what’s happened, as Ed said, unfortunately, sometimes it takes the attention, the public attention of a celebrity or sports figure or a pastor who dies by suicide, and then the conversation kind of gets revived again. Um, on the positive side, that’s great. Anything that we can talk about, we can deal with things that don’t get talked about, that don’t get dealt with. They stay underground, they fester, and people die in, in shame and alone. So it’s exciting to me to see the number of people, pastors who are talking about their own mental health, talking about their own mental health struggles. There, more support groups springing up in churches, um, more churches are open to letting people tell their own lived experience. So I see a lot of positive movement. I think it’s headed in the right direction, except probably around suicide and suicide training. I think we’re still almost at the very beginning there, which is why I love what Living Works does. And I love the specific training, but I do see a positive trend.

Glen Bloomstrom:

Well, I’ll just answer that. I’ve been working quite a bit over the last several years with rural churches, and primarily up here in Minnesota with the major group up here, the Evangelical Lutheran Church. And I just found I have found there is interest and there are are pastors, clergy. I’ve been in North and South Carolina as well. There just this whole topic of mental health, especially among the older generations. They were never trained in this. And in fact, Matthew Sanford has done research. It’s 2014, but he found that it’s still in most seminaries. There’s one pastoral counseling class. That’s it. And it’s on active listening and referral. And so there’s a lot of questions about mental health, but I find that progressive churches are much more interested in suicide prevention, and they’re more willing to sponsor suicide prevention. Evangelical churches less so, and the openness to learning suicide prevention skills. You can literally see a turning point when people take the time to learn how to listen better, rather than go on autopilot, that, you know, if the only thing you have is a hammer and everything looks like a nail, you know, pastors mean well, but they don’t listen as well. Make quick assumptions about what’s behind the presenting issues. And so without training, suicide is not even on the radar for many. So that’s been my experience. But also I love to see the turning point when people get the training and they have an aha moment and they feel ready, willing and able to ask about suicide.

Ed Stetzer:

Yeah. And I think it’s, um, it’s worth noting that when you say a progressive churches are better at this, you’re far from a progressive church. I mean, you’re at a very conservative evangelical bastion. Um, and, and, and this conversation, the reason we’re having this podcast is K texted me and she said, you know, what does Talbot do about suicide prevention? I think after you guys had some meeting or conversation. And so I, you know, I’m relatively new here. So I emailed our team and they put together a really helpful response. Turns out we have multiple points that we engage the conversation. But still some areas that I want us to lean in on more. So just back to you, Glenn. So what what are some of the because again, this is part of your advocacy is, is that schools like mine, like Talbot School of Theology, should and can do better. And I and I’m going to say yes, and I agree. But right now our audience that’s listening are pastors and church leaders. So let’s ask first what mistakes? Maybe one’s not listening well, but what mistakes do you see? And then what are churches when they’re doing well in this area? Pastors and and churches are doing well in this area. So let’s just start with what are beyond the not listening. Well, what are some of the mistakes that that pastors and churches make? And then on the flip side, what can we do?

Glen Bloomstrom:

Well, well, let me just say that, you know, we do the best we can in seminary. There’s only so many hours you can put into a 3 or 4 year program. And at Bethlehem we have a four year program. And at one point we had three pastoral counseling classes. And our second class really dealt with issues that would prevent present themselves. And I would always have our students look at Christian literature, faith based literature that come from organizations like CCF and then but also tell me what is out there that the secular world is learning that you need to know about. And so I think in these areas of mental health and suicide, it’s an on the job training. It’s after graduation because many of our students, when we were learning, you know, counseling skills and a lot of my training was secular. So I focused really on the structure and the process of a conversation. And my partner, who is a biblical counseling and knew the literature well, he was able to integrate much of that biblically biblical counseling material. And we had a great thing going. And so I think that it comes from being in a study group. It comes from learning, maybe a model that guides you from the beginning to an end, to think more broadly, more holistically. What is this person bringing? So I think it’s OJT JT, and I think that you need to take a training that is evidence based and that has a long track track record of effectiveness. We see many programs popping up. We see many programs that are information based, but they’re not teaching the skill. Where am I in this conversation? What comes next? What should I answer? And a way to get back if you’re out of sync, so to speak? Yeah.

Ed Stetzer:

And let me just say we’re unapologetic saying too, that people can and should. We’ll put it in the links and go to. They can go to check out Livingworks. Net but I think your point you’re being very generous. There’s there’s others. But the point is to have something substantive in our training more than simply, I’m going to meet with you. I’m going to listen to you. I’m going to refer. But there’s more that we can do. So, but I want to press in a little bit on that. What more? Let’s go to Kay and then we’ll come back to Glenn. What more can we do. What does it look like when this goes well. Because you know that. And we’ve even talked about this, that this can pastors worry that they’re going to be overwhelmed with mental health concerns, you know, concerns people are struggling. Et cetera. Et cetera. And so sometimes the referral is almost like, so I don’t have to do the bear one another’s burdens part. So what does it look like to sort of find that right space where a pastor or church leader, you know, the staff member he or she is, is is attentive appropriately? What does a a good strategy look like? How how now shall we lead.

Kay Warren:

Mhm. I love what you just said there because I think probably one of the number one reasons that more pastors don’t pursue this is because there’s a pass the buck mentality.

Ed Stetzer:

The sets are church leaders podcast is part of the Church Leaders Podcast Network, which is dedicated to resourcing church leaders in order to help them face the complexities of ministry. Today, the Church Leaders Podcast Network supports pastors and ministry leaders by challenging assumptions, by providing insights and offering practical advice and solutions and steps that will help church leaders navigate the variety of cultures and contexts that we’re serving in. Learn more at Church leaders.com/podcast network.

Kay Warren:

It’s not my it’s a medical problem. You know, it’s the flip side of the good progress that’s been made. Whereas there’s a more there’s more acknowledgement that mental illness is real, that it’s not something you can just make go away. So the acknowledgement that that it is a medical problem, a part of health has then led to some clergy deciding, well, then that’s not mine. That’s a medical thing, you know. So there’s the pass the buck. It’s not mine to do. And I love what John Swinton, you know, Doctor John Swinton, one of my mentors, has he has a very simple statement that he said, as long as we frame this as, oh, there’s a person with a mental illness, then clergy can say, are not mine, you know. Interesting that pass the buck. But if you flip the emphasis within the sentence to, oh, there’s a person with a mental illness, then it sits right smack dab in the purview of the church, because the personhood of an individual that is, that’s our in our DNA, that is what we are called to speak to, is the person. The medical community isn’t called to speak to the personhood of a, of an individual, but the church is. So when pastors, I think, take seriously the call to care for people at, at their soul level, at at their, at the core of who they are and come alongside of them in some of their most deep distress. The crisis of soul, the crisis of of well-being, the crisis of meaning and purpose. That is where we speak to people the best.

Kay Warren:

And when pastors recognize that the call is not necessarily to be involved in physical medical health, but to be care for persons who are struggling. Then I feel like all of their other arguments about, well, you know, it’s a medical issue or there aren’t that many people affected, which is wrong because there are at least 45 million just in the United States alone who are going to be diagnosed with a mental illness next year. That’s not fringe. Um, when it gets rid of our concerns about, oh, I don’t know, a program or I wasn’t trained, it really comes down to a decision. It comes down to a commitment, an intentional decision to see that the role of Shepherd in a church is to care for vulnerable people in their weakness, in their suffering, in their distress and mental illness and suicidal thoughts. Absolutely places people in, um, in deep distress. So for me, it’s Shifting. Once they’ve made that decision, then they need the skill training. But if they don’t come to a place of recognition that this is in your purview, this is not a fringe issue. This is affecting people in your congregation right now. If you have a church of five people, one of them is living with a mental illness. So it’s very common. And so to me, the where I come at it from is promoting skill training that others have come up with, but also speaking to pastors and church leaders to say, this is your business, this is your business.

Daniel Yang:

Glenn, let me ask you, because you’ve been in sort of training denominational leaders and organizational leaders around this. What are some of the prevalent misconceptions people have about suicide? And then, um, in the aftermath when someone loses somebody close to them, how does their ideas around the topic change?

Glen Bloomstrom:

Well, generally it takes a death or a serious attempt before people start to pay attention. That’s the bottom line, and I think all of us know that if we’ve had any experience, you know, our experience in the church, in ministry settings. But the misconceptions are only certain types of people, you know, but we really want to advocate that anybody can be at risk. And so if you put up a slide with the the statistically more prevalent people, well, those are the only ones you’re going to look for. But if you say that anyone can be at risk for suicide, and then secondly, that it always involves mental illness, it doesn’t it can be a life crisis. It can be.

Ed Stetzer:

And that’s that’s so key though. But people aren’t aware of that. So I’m sorry. Keep going. Didn’t interrupt but it’s so key.

Glen Bloomstrom:

And really, one author said he began an article by saying suicide is one of those words that feels jarring to write. To see in writing or to say so people go to informational based training or just ask. About suicide. But even the skill based training, it’s hard for people to say, are you? Thinking about suicide? You need to practice doing that. So, um, that and then finally that there’s nothing one can do. Or if you ask somebody about suicide, you’ll put it in their mind. Well, those are all myths. And instead, if they’re not suicidal, they say, whoa, you just noticed some things happening in my life. I didn’t realize I was coming across like that. No, I’m not, but it strengthened the relationship. And the only way you’re going to ask and use the word suicide is if you’ve been trained and you have the confidence to step into that very uncomfortable place.

Ed Stetzer:

And a lot of that training we’re not assuming. Although, again, I think seminaries can and should do better. But where we keep coming back to that on the job part of that as well. And again, we’ll put we’ll link to the resources. Okay. Glenn, I noticed you mentioned your military connection was intriguing to me. One of the reasons I wanted to have you on is a few years ago, when General Carver was the army chief of chaplains, we I think we were probably at the same meeting. I spoke at the Army Chief of Chaplains training meeting, and one of the things that stood out to me, that was not my topic, but one of the things that stood out to me was how different the assumption was that the army chaplains would not always refer. Whereas I got to tell you, I mean, and this is where I’m going to get to Kay in just a minute, because I think I’m trying to understand a little bit the messaging here, because the message for many of us was you got to refer, but now the message is and that was not the when I was with the chaplains, that was not what I mean. There were certainly times for mental health crises and diagnosable mental illnesses. So? So what? I mean, what can we learn from that military experience where, you know, over overwhelmingly young, disproportionately young men, but high suicide rate, high suicide, suicidal ideation. But the whole training was different. Talk to me about that.

Glen Bloomstrom:

Well, one of the primary elements of being a chaplain is when you’re speaking to your soldier, they don’t know if you’re Catholic or Protestant or what. And so whether you’re a chaplain or a chaplain assistant, you have 100% confidentiality. And so most of the times when soldiers would come and speak to any chaplain, including me, it always begins, chaplain, I’m not very religious, but and then they start to talk to you about things. So we had confidentiality. And across all of DoD, we’re going to listen. And if they’re thinking of suicide, we don’t immediately just take them. We’re going to try to convince them to self self refer, but we’ll go with them. They’re the ones that need to break confidence, not us. And so even in my training now, I was with a bunch of police chaplains in the last few days at a large conference for the International Council on Police Chaplains. And, you know, they’re in that same, same space because no one wants to be labeled. They don’t want to lose their job. And it’s the same thing with military. And so we’re going to sit with them, we’re going to work with them. We’re going to hold that confidence. Whereas and we believe that because we have this relationship, we can we’ll explain what’s going to happen, we’ll make it safe, we’ll go with them and they will break the confidence. And that keeps our credibility that we don’t tell the command, we don’t go beyond what happens in our room, so to speak.

Ed Stetzer:

I tell you, I was fascinated by the by the meeting and the training and how it was all navigated, but okay, you sort of heard me leading to this, but so here’s and I think in part my hypothesis is that as evangelicals, um, started to take mental illness more seriously, part of what we were kind of teaching them is that maybe your seminary preparation didn’t help you to appropriately equip you to deal with some specific diagnosed mental illnesses. So we sort of were persuading them to refer, and that was good. But then I think the message overcorrected to where now it’s and I think sometimes it’s the concern of being overwhelmed. I think sometimes it’s a concern of like, I don’t want to be responsible for all of those things as well. So how do we, you know, if the pendulum and maybe I’m wrong? That’s my hypothesis. I’d like to know yours. And then how do we get the pendulum at the right spot?

Kay Warren:

No, I do think that’s exactly what’s happened. At least that’s what I’ve observed. I don’t have any research on it, but that’s just anecdotally, what I see is that the pendulum swing swung, went too far into, like I said, to the pass the buck. You know, I see that you need help. Oh, but I don’t know what to do. So I’m going to or I’m too busy or I’m too overwhelmed or whatever. I’m going to send you on to someone else. And there’s it’s a both and. We want pastors and church leaders and staff to recognize someone is in distress, that they are in serious distress, and that they need more than they might need more than what you have to offer them. So you need to know how to connect them to properly trained people who can help them further. But that doesn’t mean then it’s just like, and you’re done. Because there is a role for shepherds in every stage of a person’s life, and particularly somebody who’s struggling with depression or suicidality. There is a role as as Glenn was just saying, of comforting, of listening, of really entering in. Um, pastors do need to learn how to listen better. Um, it is not just a matter of what surface. It’s understanding that here is a person who’s suffering and struggling, so there’s a level of compassion. Then there’s a level of, and we’re not going to leave you alone. We’re not going to just send you off to a therapy or to a psychiatrist, or even make sure you get to, you know, an emergency department who can help you because you’re in immediate crisis. That is all vital, absolutely vital. Um, but there is a continuing role of shepherds to care for people as they are in their distress. And so that’s the both end. Okay.

Ed Stetzer:

So help, help the pastor and church leader. So someone’s at first Wesleyan and they’re like, okay, so I want to do what I hear Glenn and Kaye talking about, but like, what would that look like? So am I someone’s dealing with, let’s say in this case, a depression is is connected to suicidal ideation. Um, so is that should I touch base with them once a day? So I touch base on once a week. Again, I’ve recognized that maybe they need additional help and I’ve helped with that, but I’m not. But by the way, for those of you listening on a podcast, when you might have heard that noise, that was Kaye using a hand signal as she’s washing your hands. So so we so we don’t want to wash our hands, but I want that. So someone from First Wesleyans across the table from you and say, well, okay, how often should I make sure? How do I make sure they’re cared for as an addition? They’re getting appropriate mental health counseling as well.

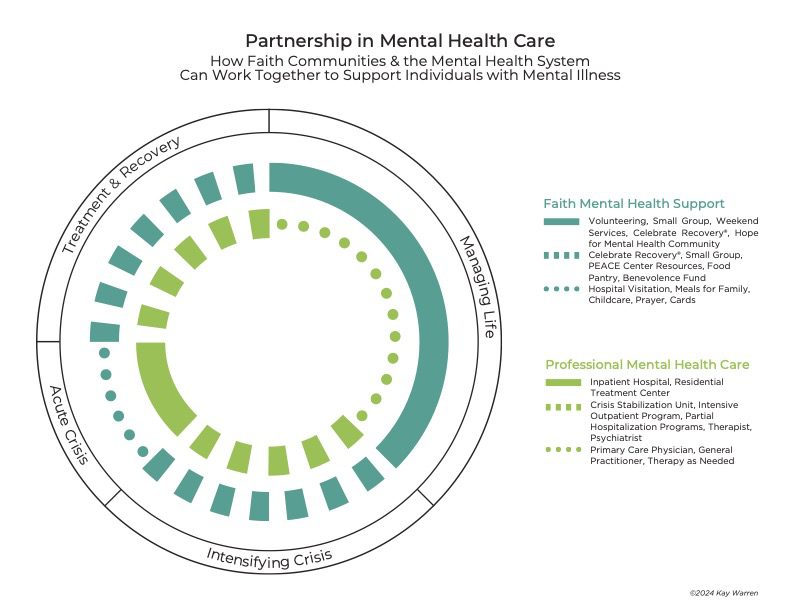

Kay Warren:

Well, um, um, I, I have a diagram that we might want to include in your, in your show notes. Yeah, we can put it in the show notes. Yeah, it’s hard.

Ed Stetzer:

But you can if you can verbally explain it. Because, you know, most people listen to my podcast, not video. Tell us.

Kay Warren:

Yeah, absolutely. Well, there’s just there’s a continuum of care if somebody is managing their life, maybe then the role of the church is, you know, you’re helping them through. They’re engaged in a Bible study or support group, and particularly talking to somebody who might have some, you know, mental health challenges or somebody who’s just not who’s doing pretty well, but, you know, they just need a little help. So so they’re involved in the church, they’re a volunteer. They’re at a weekly, you know, church service. They are they’re serving. Maybe they’re part of a celebrate recovery, maybe they’re volunteering. And then as they maybe go into a crisis, the role of of mental health professionals starts to increase and the role of the church. So it shifts a little bit. So now there’s a mental health professional in some way involved. And the church is still there in caring, in connection, encouraging them to come when they can. If that person continues to move into crisis, then the role of the mental health team increases, where the role of the church is a little bit smaller, because what they really need right then is more of it.

Kay Warren:

But it’s not that the church goes away. Maybe the church provides meals. Church makes sure that they’ve got somebody writes them a note, somebody gives them a call. Somebody is making sure that their kids are taken care of, that, that their wife is given a ride to the to see them, visit them. And then as they move into recovery, it begins to shift a little where the role of the mental health professional goes down a little or the role of the church increases. So then you move around this continuum in tandem with one the mental health role, professionals role, and the church role kind of just adjusting to each other all through that spectrum of care. So there’s never a time in which the church is not engaged. And and there’s always a place in which the mental health profession is, but they just shift in their roles as they go around the continuum as someone is doing well, doesn’t do well in crisis recovery, and then returns to stability.

Daniel Yang:

I can imagine a church leader or pastor listening to this now and feeling really convicted and being able to take a next step. And Glenn, I’ll go to you. Um, maybe before anything is even implemented or a tangible next step, what are some things that a church leader or pastor should know as they get ready to engage in becoming more aware and engaged in helping their church become more aware around suicide prevention?

Glen Bloomstrom:

Well, the two things that I would want to stress very simply, I’ve already done one, and that’s training, but the other is collaboration. Kay is an example of the greatest advocate, and I think, Ed, you are too, because of your story. You’re into this subject because I read your article and I know about your family a little bit. When you are bereaved survivor, you can become an advocate for these kinds of things. And this is where pastors can learn. When we come alongside of someone who has a diagnosis, we learn about anxiety and depression. We see that it’s bigger than, you know, the DSM five. But here’s the thing. A pastor in a small church in a rural area think, oh my goodness, another thing on the plate. Oh, how can I follow up with 2 or 3 different people? Well, that’s where we have to find people in the church who have lived through this experience in the church. And then we have to collaborate with other churches. There are some pastors that are really super excited about suicide intervention. So there’s different levels of training for different roles. And so you have a shorter training for people that visit shut ins or that work and host youth in their home. And the youth pastor is in a mid level, and maybe that pastor will be trained at the highest level like a crisis line worker. And if not, that, pastor will be a pastor from the neighborhood.

Glen Bloomstrom:

I’ve got a story. A youth pastor went through a training in a small northern Minnesota town. He was a youth pastor. He was very young. But this town, everybody got along as far as the different churches. There was a death in a high school or a middle school. The principal went to that church. Some of the other pastors said, called up the youth pastor and said, well, what do we do? Well, actually, the principal was a member and said, okay, what do we what should we do? That youth pastor knew enough to provide the principal, who was a new principal, with some do’s and don’ts and things to do in the school. Then all of the clergy came together. They all supported that school together because they got in the same room and talked about, okay, what now? What if dos what are don’ts? And so I think if you have a network of, of churches in a rural area, like a lot of our Lutheran churches or free church churches here in rural Minnesota, where and in South Carolina and North Carolina, let’s work together. Yes, we have differences, but can we agree that saving a life from suicide is something we can agree on, and we can all host trainings, and we can all find out who’s gifted and who has advocates in their churches and work together.

Kay Warren:

Can I just can I just add to that? I love what Glenn just said, because there’s a role for church members. The average church member can learn in a in a four hour training, um, how to recognize that their neighbor or their loved one or their coworker is struggling and really needs some help. Everybody can learn that there are some things that everybody in a congregation can learn, and then there are some things that other staff can learn at a little bit higher level. And then, as Glenn said, maybe every church in the area doesn’t have a trained trainer, but some do. That collaboration that that every church can do something every member can do something. Every staff member has a call to care and to be able to recognize. And the training is is available. It’s there and it saves lives.

Glen Bloomstrom:

And there’s just something so good about churches agreeing to work together for this particular issue. And it could spill over to other kinds of recovery or, you know, abuse or anything like that, you know.

Ed Stetzer:

Yeah. No, I agree. I think this is, again, a super helpful conversation. We’ve gone a little longer than normal because I think this is important stuff to cover and also to I know most of you listening to this as a podcast and you just got your phone and you listen to this podcast, but if you don’t mind this time, go to some of the resources and we’re going to put resources and links from Glenn and Kay both at the well where the episode guide is. But also if you go to Church leaders.com/podcast, you can find it there. Go to this particular episode and we’ll have have those resources there. Um, I guess to ask one sort of closing question, what, you know, you’ve got pastors and church leaders, uh, audience here. Um, you know, what what exhortation would you give to them from your. And we’ll start with Glenn and then, Kay, you know, your journey has been so public to all of us. So a lot of us know the story. But, Glenn, last exhortation from you to pastors and church leaders.

Glen Bloomstrom:

Don’t be afraid of suicide. You can be trained to be willing, ready and able to have that conversation. Also, we let’s don’t be afraid of litigation or the possibility that one of our people will die even after we’ve helped them. Don’t be afraid. Be trained and have a protocol. If you are going to refer somebody who have you talked to? What will happen? Will it cost money? So step into the space on the job. It won’t overwhelm you. And then pray that God will provide other people to collaborate with you from your church or from other churches.

Ed Stetzer:

Okay, I don’t think I ever, um, you know, Glenn mentioned that article I wrote. I don’t think I talked about any of these things until you and Rick talked about these things. And I wrote that article in CNN that will link there where I had a person in our church who’s, uh, died by suicide, and then my own aunt and others. But I think you gave us all permission through your own pain to talk about those things. And I think the church is better for it. What closing words would you have for us?

Kay Warren:

Um, I’ve just thought through this whole conversation of Ezekiel 37 and God’s word to shepherds. It was, um, first a demonstration. You have not cared for my wounded sheep. I will care for them. And then going on for him to just say, care for my sheep, bind up their wounds. We can do this as shepherds. This is not as Glenn said, this is not an insurmountable topic to tackle or to be trained in or to make a difference. Shepherds, we are called to tenderly bind up the wounds of the sheep.

Glen Bloomstrom:

Amen.

Daniel Yang:

We’ve been talking to Kay Warren and Glenn Blomstrom. Be sure to check out the resources available at Koin.com and the Action Alliance. Org and thanks again for listening to the Stetzer Church Leaders podcast. You can find more interviews as well as other great content from ministry leaders at Church leaders.com/podcast. And again, if you found our conversation today helpful, we’d love for you to take a few moments to leave us a review that will help other ministry leaders find us and benefit from our content. Thanks for listening. We’ll see you in the next episode.

Voice Over:

You’ve been listening to the Stetzer Church Leaders podcast for more great interviews as well as articles, videos, and free resources, visit our website at Church leaders.com. Thanks for listening.

Sonix is the world’s most advanced automated transcription, translation, and subtitling platform. Fast, accurate, and affordable.

Automatically convert your mp3 files to text (txt file), Microsoft Word (docx file), and SubRip Subtitle (srt file) in minutes.

Sonix has many features that you’d love including share transcripts, advanced search, automatic transcription software, collaboration tools, and easily transcribe your Zoom meetings. Try Sonix for free today.

Resources from Kay Warren and Glen Bloomstrom

Partnership in Mental Health Care diagram from Kay Warren:

PDF of Kay’s diagram: Partnership in Mental Health Care

LivingWorks Intervention Training options:

LivingWorks ASIST – two-day comprehensive intervention training that includes an intervention model and safety planning. This is the training that most crisis line workers are trained to use.

Key Questions for Kay Warren and Glen Bloomstrom

-What changes have you observed over time in how the American church addresses mental health challenges, specifically suicide and suicide prevention?

-What mistakes do you see that pastors and church leaders make when it comes to suicide prevention?

-What does a good strategy look like in this area?

-What are some of the prevalent misconceptions people have about suicide?

Key Quotes From Kay Warren

“It’s personal. These are people I love. These are people that meant something to me and that their lives became so painful and unmanageable and they felt they could not go on—they’re really just a microcosm of the millions people of people around the world, about 51,000 or so in the United States who take their lives every year.”

“It’s a hard topic to talk about, but just because it’s hard doesn’t mean it’s not vitally important.”

“Anything that we can talk about, we can deal with. Things that don’t get talked about, that don’t get dealt with, they stay underground, they fester, and people die in shame and alone.”

“I see a lot of positive movement. I think [awareness of mental health challenges] is headed in the right direction—except probably around suicide and suicide training. I think we’re still almost at the very beginning there.”

“I think probably one of the number one reasons that more pastors don’t pursue this is because there’s a pass the buck mentality.”

“The medical community isn’t called to speak to the personhood of an individual, but the church is. So when pastors take seriously the call to care for people at their soul level, at the core of who they are, and come alongside of them in some of their most deep distress, the crisis of soul, the crisis of wellbeing, the crisis of meaning and purpose, that is where we speak to people the best.”

“It comes down to a commitment and intentional decision to see that the role of shepherd in a church is to care for vulnerable people in their weakness, in their suffering, in their distress. And mental illness and suicidal thoughts absolutely place people in deep distress.”

“If you have a church of five people, one of them is living with a mental illness.”

“Pastors and church leaders…this is your business. This is your business.”